BTW: The Ongoing Fight Against Family Vlogging (Part 2)

Utah is now the fourth state to implement these labor laws

This is a continuation of my previous post, sharing the talk I gave at Flagler College on March 12 about the dangers of family vlogging. You can read part one here:

BTW: The Ongoing Fight Against Family Vlogging (Part One)

On March 12, I gave a keynote address at Flagler College on family vlogging, and longtime readers know of my own advocacy work in this space. I thought I’d share my talk here in newsletter form, so everyone can hear what I was speaking about.

Part Two

Again, to think back to the days of “traditional” entertainment we discussed earlier, a child starring in a movie knew (or at least had explained to them) that large audiences would see their work. The child worked with a director, an agent, and a studio to have gatekeepers in place. Today, parents become all of those things for sharing their children online. Sharenting brings with it its own plethora of risks, but again, those risks are compounded when we have larger platforms and financial incentives.

This is why our third way of looking at family vlogging is to understand it as “not just appearing in mom and dads’ videos for fun” but a form of child labor. As I’ve already discussed, media institutions engage in boundary work to relegate content creation and influencing to “unserious” work, and that includes family vlogging.

However, I currently teach one of the only “how to be a content creator” classes in the world, in which I teach students the professional skills needed to understand work, labor, and careers in content creation and influencing. Ask me how hard it was to get this class on the books. It took years – which again, demonstrates the belief that content creation is unserious. But ask my students how they feel about this about three weeks into the class. I love my students dearly, but most of them sign up for this class too thinking it’s an easy A. They don’t realize what the work of doing content creation entails.

As I’ve written in an upcoming book chapter about what influencer and content creator production looks like: “Until one makes enough money to outsource tasks, they must perform all these skills themselves. An influencer is not just the ‘on-screen talent’…but until they can outsource other jobs, they must be their own manager, scheduler, scriptwriter, accountant, brand safety expert, video editor, data manager, and distributor, among others.” To be a successful influencer or content creators means making your own content schedule, writing scripts and storyboards, filming (sometimes multiple times to get the perfect shot), editing – that’s the part my students hate the most – then navigating algorithms, engaging with followers, negotiating your own brand deals, managing the money and taxes that come in from that, buying the best equipment, and more – all in addition to being the “on screen celebrity.” To again make a comparison to more traditional entertainment media systems, content creation and influencing merges “above the line” and “below the line” work, with above-the-line work being the big-name star talent that draws views to a media product (such as an actor or director), with below-the-line labor being technical expertise of cameramen and women, lighting crews, location scouts, and more. So in the Devil in the Family trailer I played to start this talk, when Shari Franke sets her home felt more like a set, this is the labor she is referring to.

But a key difference in these entertainment media comparison lies in distribution. We’re not working in a realm that involves TV pilots being picked up by networks or streaming services. We’re not a film seeking a distributor for movie theaters. We are talking about for-profit social media platforms that turn user content into data, which in turn are sold to advertisers. We are talking about algorithmically-driven systems, in which certain content is prioritized over others, and we have come to understand that algorithms have been programmed to love child content. Once again quoting Internet anthropologist Crystal Abidin, “As such, unlike other child-centered parenting blogs which are useful feminist interventions to value domestic labour or resist the societal pressures and ideal constructions of ‘good motherhood….constructing commercially viable biographies of children on YouTube can potentially be exploitative as children are framed to ‘maximize advertorial potential.”

Abidin draws a crucial distinction here between the early days of mom blogging and today’s pervasive culture of family video blogging. While the early mom blogs of the internet shared information about their children, and this can still be problematic, this was primarily textual based. Sure, sometimes photos were shared, but this was the exception, not the norm. But the internet is an increasingly visual medium, and images of children become popular and popularized – they are sought out by viewers and rewarded by platforms themselves. This creates a tension between mothers and parents using their stories to build community and resist dominant narratives, and the sharenting co-creation of children who brought into online being by their parents words and the labor of producing picture-perfect Instagram shots of their childhood experiences.

So we can understand family vlogging as existing at the intersection of modern-day influencing and content creation, sharenting, and the actual work and labor of it all. Through this lens, we can return to the Coogan Act, which again exists to protect children who have been hired to work as “an actor, actress, dancer, musician, comedian, singer, or other performer and entertainer” Through what I have discussed so far, I hope it is becoming apparent how family vlogging fits into the category of “other performer and entertainer.”

And well, in 2023, the state of Illinois thought so, too.

In summer 2023, Illinois became the first state in the U.S. to amend the Coogan Act to include family vlogging and the children of influencers and content creators. Illinois is one of the nine states that has a version of the Coogan Act, and it became the first to lead the way in protecting children under these new forms of labor and entertainment.

This monumental change came to be because during the height of the COVID-19 lockdowns, sixteen year old Shreya Nallamothu from Normal, Illinois was scrolling social media and becoming increasingly frustrated with the amount of family vlogs she saw online. She later told the Associated Press, that “she recalled the many home videos her parents filmed of herself and her sister over the years: taking their first steps, going to school, and other ‘embarassing stuff.’ I’m so glad those videos stayed in the family, she said. ‘It made me realize family vlogging is putting very private and intimate moments on the internet. The fact that these kids are either too young to grasp [social media’s permanence] or weren’t given the chance to grasp that is really sad.”

So Shreya wrote a letter to her state senator, Dave Koehler, urging him to consider introducing legislation to protect the children of family vloggers and the internet’s youngest content creators. He did. The bill moved through the state legislature, and was signed into law by Illinois’s governor J.B. Pritzker in August 2023.

Starting on July 1, 2024 – so the law is almost a year into being in effect – parents in Illinois are required to put aside 50% of earnings for a piece of content into a blocked trust for their child, based on the percentage of time they are featured in the video. For example, if a child is in 50% of a video, they should receive 25% of the funds; if they’re in 100%, they are required to get 50% of the earnings. However, this only applies in scenarios during which the child appears on the screen for more than 30% of the vlogs in a 12-month period.

The Illinois law was sensitive to the fact that a copy and paste of the Coogan Act would not be effective or equitable to apply to family vlogging. After all, parents are in the videos too and should receive compensation, and even if they’re not, they are still the ones filming, editing, and managing the social media post – a.k.a. doing that “below the line,” technical labor I talked about earlier.

But of course, this bill is not perfect. No law is. Shreya herself, alongside Quit Clicking Kids non-profit founder Chris McCarty, have both gone on record saying future laws should move beyond the financial to consider the issue of consent. And I agree.

In my work in the family vlogging advocacy space, consent is an issue that arises time and time again. It is largely understood in American society that minors are not capable of consent. As such, their parents are the ones responsible for their well-being and giving or not giving consent on their behalf. In family vlogging, this creates a muddled terrain with competing interests. The parents’ aspirational labor is at odds with the child having a protected, private childhood. This is another huge difference between the original Coogan Act and these laws protecting content creator children – Hollywood actors play fictional parts. The children of family vloggers have their own experiences put online for millions to see.

So as work in this space continues, some states have considered that.

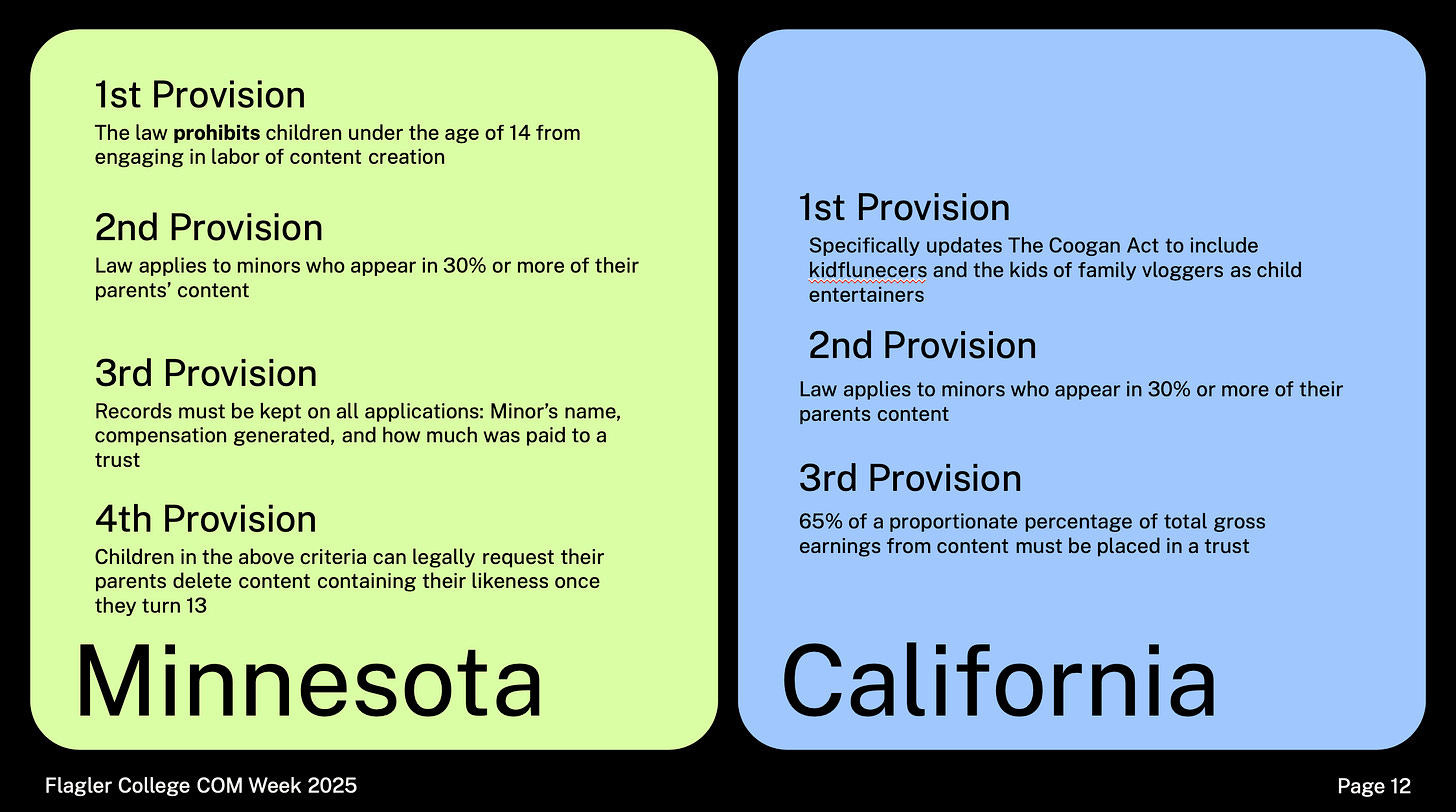

In 2024, Minnesota became the second state in the US to pass a law protecting the children of family vloggers. Like Illinois, the bill requires a trust account for the payment of social media content using the child’s likeness. The bill would require that records be kept on minors who appear in at least 30% of the content creator’s videos, when such videos generate income, including the minor’s name, compensation generated, and how much was paid to the minor’s trust account.

But where Minnesota goes a few steps further than Illinois in two main ways. First, the law prohibits children under the age of 14 from “engaging in the labor of content creation.” However, the balance this with broader practices of sharenting, and parental rights to sharing their parenting experiences online, a child is to appear in no more than 30% of a content creator’s content in a 30-day period, and if the number of views received per video segment meets the online platform’s threshold for the generation of compensation or the content creator received actual compensation equal to or greater than $0.10 per view.

The second way the Minnesota law differs from Illinois is that it gives children control over the content they’ve been featured in once they turn 13. At 13, the child is allowed to request deletion of content featuring them at over the 30% mark, and parents must comply. This is a key provision that I will discuss more in depth on the subsequent slides. The Minnesota law will go into effect on July 1st of this year.

In December of 2023, I was personally contacted by California State Senator Steve Padilla, who had been tracking this legislation that had been cropping up around the country. Senator Padilla reached out to me because he was introducing legislation to update and modify the Coogan Act for the social media age, and he invited me to consult on drafts of the bill. It was my great honor to do so.

In my conversations with the Senator and his staff, we discussed a few key elements of the potential legislation. One was terminology, and how even though researchers in my line of work note the differences between terms like influencer, content creator, and family vlogger, the public uses these terms interchangeably. Another major point of discussion was location and enforcement. Obviously, the laws of California can only extend to California’s borders. This means that a family that vlogs who lives in California would obviously be subject to the law, but if they traveled for a family vacation and made content, would that content be subject to this law, and if it was, how easily could it be enforced? These are also part of the new challenges brought by social media entertainment, and again, how different this type of child entertainment labor is from the Coogan Act.

In the end, the law was written to be as strong as possible without reaching past California’s jurisdiction. The law passed the California legislature in fall 2024, and was signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom in December 2024. It went into effect on January 1st of this year. This law includes a higher proportionate percentage than the previous state laws at 65% into a trust. This is extremely notable given that California is a hub for influencing and content creation.

But the one I’m really watching right now is Utah. Last year, Kevin Franke – yes, estranged ex-husband of Ruby Franke, who we watched in the beginning of this talk, began working on the law, HB322, with Utah Representative Doug Owens. Around the same time, last summer, Kevin Franke called me.

Kevin and I talked on the phone for several hours about the dangers of family vlogging. It was a startling conversation, in which we both agreed that family vlogging can exploit children, particularly those who already in potentially exploitative homes. Kevin and his eldest daughter, Shari Franke, worked extensively to champion Utah’s family vlogging legislation. I also provided written remarks on the record in support of HB322. And this past Friday, on March 7, the state legislature passed HB322. Some provisions were pared back from original drafts, but the bill is still strong. The bill sets up a system for children to be financially compensated if they are featured in monetized social media content. In order for parents to be required to pay their kids, the child has to be in at least 30% of the content and making $20,000 a year. The parents also have to be clearing $150,000 a year after expenses. And while that number seems steep, remember that is not uncommon for family vlogging YouTubers to net over $20,000 per singular video. This means that if they’re posting even once a week, they will easily clear that threshold.

However, Utah also includes a right to be forgotten provision. HB322 would make it so children who are featured in content can request for that content to be taken down once they turn 18.

The provisions are notable in Utah, which has more family vloggers per capita than anywhere else in the world. Similarly, Utah is a mega-popular influencer hub – I don’t know if anyone in here watched The Secret Wives of Mormon Wives and is familiar with #MomTok – but the relationship between Mormonism, influcning, and family vlogging is no accident, and I’m happy to talk more about that in Q&A.

The Right to be forgotten has emerged over the last two decades as a key component to our digital lives. The right to be forgotten is distinct from the right to privacy. The right to be privacy constitutes information that is not known publicly, whereas the right to be forgotten involves revoking public access to information that was once publicly known.

The United States currently has no right to be forgotten laws – because Minnesota and maybe Utah’s laws have not gone into effect yet. They would be the first instances of such provisions in this country.

However, the European Union has had grappled with various iterations of the right to be forgotten for over fifteen years now. EU countries have beholden to the GDPR, or the Gross Data Protection Regulation, which governs how personal data must be collected, processed, and erased by social media and tech companies. After caselaw in 2014, the right to be forgotten was specifically included in the GDPR. While the GDPR gives internet users more agency over their data than we as US users have, it was originally applicable only to data, not necessarily content. That 2014 caselaw changed that. At present, France has some of the strictest interpretations of this law, with right to be forgotten law enacted in 2010. France also introduced legal protections for the children of family vloggers in 2020. Their laws are quite punitive. Whereas in the US, the recourse for violating these family vlogging laws just gives children the right to sue their parents, French parents can face fines up to 75,000 euros and up to five years in prison. Advertisers also face new restrictions. If they want to place products in videos featuring children under 16, they must check whether the money should go to the person in charge of broadcasting or to the child's blocked account — or face a €3,750 fine.

But the Right to be Forgotten in both Europe and the US lets social media platforms themselves off the hook. This is something, that, in my opinion, must change if we’re to protect children in a world of family vlogging. Of course, platforms right now are not incentivized to not do so. Family vlogging is huge business for them. The goal of platforms is to keep you on their specific site for as long as possible, and family vlogging is lucrative and enticing content that keeps people interested and unable to look away. Family vlogging is great for social media business models. But this means platforms are playing a role in exploiting children as well. A question I always get asked in interviews and in testimony about these laws is tracking and enforcement. People always ask, “who’s going to keep track of these percentages?” “How can we prove where a video was filmed to see if it’s in compliance with state law?” And my answer is an easy one – social media platforms themselves. They have access to all of that backend metadata, as well as video scanning technologies used in content moderation.

The follow-up question is always, “Well, isn’t that a big ask for platforms?” Of course it is. But why should platforms themselves not play a role in making their spaces safe for children? As Australian Internet Researcher Tama Leaver notes, the burden of educating children about social media and internet privacy falls almost exclusively to parents with no systemic social support. It becomes another difficult, hard-to-understand situation for parents to navigate without support. And we should be supporting parents in these endeavors. It’s time for social media platforms to step up.

I always tells people this: If they can build a Metaverse, they can build a taskforce or a unit to comply with these family vlogging laws. If they build Grok AI, they can monitor metadata for how long a child has appeared in the video. This isn’t a difficult decision. But the fact platforms haven’t been willing to step up and be on the right side of history demonstrates skewed priorities. In fact, at present, I can tell you that the tech lobby is one of the biggest advocates against the family vlogging legislation work that is being done.

And so, I’ll wrap up with this today. One of my personal favorite reads about considering childhood online is The End of Forgetting: Growing up with Social Media by Kate Eichhorn. And in this book, she says, “The internet never did make childhood disappear. Today, childhood and adolescence are more visible and pervasive than ever before…the potential danger is no longer in childhood’s disappearance, but rather the possibility of a perpetual childhood. The real crisis of the digital age is not the disappearance of childhood, but the specter of a childhood that can never be forgotten.”

In other words, in the early days of the internet, everyone’s fear was the children would be exposed to adult content too early, and it would prematurely end adolescence. Sharing personal information online was considered extremely dangerous. One of my formidable childhood memories is when my parents let my brother and I log on to AOL (that’s American Online, the early internet, for you youngsters in the room), they told us to never share our real names or any personal information about ourselves with anyone. Now, we live in a digital culture of oversharing, both as consumers of others’ intimate moments, and even the sharing of our own.

And it turns out, our biggest fear of childhood ending too early didn’t quite manifest the way we thought it would. I’m sure if you asked Shari Franke, she would tell you her childhood did end early because of the internet – but not because of exposure to strangers, but because of her mother’s own relationship to social media. But really, the inverse has happened. Children won’t just have their childhood innocence taken from them too soon. They’re not haunted by the childhood’s forever. We joke that the internet is forever, but it’s true. When family vloggers share their children online, they risk stunting their child’s growth and hurting future friendship, romantic, or even employment opportunities for them. We now live in an era where kids won’t grow up too quickly. Because of the family vlogging content that haunts them online, they’ll never be allowed to fully grow up at all. Thank you.